George I Of Great Britain on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

)

, house = Hanover

, father = Ernest Augustus, Elector of Hanover

, mother = Sophia of the Palatinate

, birth_date = 28 May / ( O.S./N.S.)

, birth_place = Hanover, Brunswick-Lüneburg,

, death_date = 11/ (O.S./N.S.)

, death_place = , Osnabrück, Holy Roman Empire

, burial_date = 4 August 1727

, burial_place = Leine Palace, Hanover; later Herrenhausen, Hanover

, signature = George I Signature.svg

, signature_alt = Signature of George I

, religion = Protestant

George I (George Louis; german: link=yes, Georg Ludwig; 28 May 1660 – 11 June 1727) was King of Great Britain and Ireland from 1 August 1714 and ruler of the

In 1682, George married Sophia Dorothea of

In 1682, George married Sophia Dorothea of

Ernest Augustus died on 23 January 1698, leaving all of his territories to George with the exception of the Prince-Bishopric of Osnabrück, an office he had held since 1661. George thus became Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg (also known as Hanover, after its capital) as well as Archbannerbearer and a Prince-Elector of the Holy Roman Empire. His court in Hanover was graced by many cultural icons such as the mathematician and philosopher Gottfried Leibniz and the composers

Ernest Augustus died on 23 January 1698, leaving all of his territories to George with the exception of the Prince-Bishopric of Osnabrück, an office he had held since 1661. George thus became Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg (also known as Hanover, after its capital) as well as Archbannerbearer and a Prince-Elector of the Holy Roman Empire. His court in Hanover was graced by many cultural icons such as the mathematician and philosopher Gottfried Leibniz and the composers  Shortly after George's accession in Hanover, the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1714) broke out. At issue was the right of

Shortly after George's accession in Hanover, the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1714) broke out. At issue was the right of

Though both England and Scotland recognised Anne as their queen, only the Parliament of England had settled on Sophia, Electress of Hanover, as the heir presumptive. The Parliament of Scotland (the Estates) had not formally settled the succession question for the Scottish throne. In 1703, the Estates passed a bill declaring that their selection for Queen Anne's successor would not be the same individual as the successor to the English throne, unless England granted full freedom of trade to Scottish merchants in England and its colonies. At first Royal Assent was withheld, but the following year Anne capitulated to the wishes of the Estates and assent was granted to the bill, which became the Act of Security 1704. In response the English Parliament passed the Alien Act 1705, which threatened to restrict Anglo-Scottish trade and cripple the Scottish economy if the Estates did not agree to the Hanoverian succession. Eventually, in 1707, both Parliaments agreed on a Treaty of Union, which united England and Scotland into a single political entity, the Kingdom of Great Britain, and established the rules of succession as laid down by the

Though both England and Scotland recognised Anne as their queen, only the Parliament of England had settled on Sophia, Electress of Hanover, as the heir presumptive. The Parliament of Scotland (the Estates) had not formally settled the succession question for the Scottish throne. In 1703, the Estates passed a bill declaring that their selection for Queen Anne's successor would not be the same individual as the successor to the English throne, unless England granted full freedom of trade to Scottish merchants in England and its colonies. At first Royal Assent was withheld, but the following year Anne capitulated to the wishes of the Estates and assent was granted to the bill, which became the Act of Security 1704. In response the English Parliament passed the Alien Act 1705, which threatened to restrict Anglo-Scottish trade and cripple the Scottish economy if the Estates did not agree to the Hanoverian succession. Eventually, in 1707, both Parliaments agreed on a Treaty of Union, which united England and Scotland into a single political entity, the Kingdom of Great Britain, and established the rules of succession as laid down by the

Within a year of George's accession the Whigs won an overwhelming victory in the general election of 1715. Several members of the defeated Tory Party sympathised with the Jacobites, who sought to replace George with Anne's Catholic half-brother, James Francis Edward Stuart (called "James III and VIII" by his supporters and "the Pretender" by his opponents). Some disgruntled Tories sided with a Jacobite rebellion, which became known as "The Fifteen". James's supporters, led by Lord Mar, a Scottish nobleman who had previously served as a secretary of state, instigated rebellion in Scotland where support for Jacobitism was stronger than in England. "The Fifteen", however, was a dismal failure; Lord Mar's battle plans were poor, and James arrived late with too little money and too few arms. By the end of the year the rebellion had all but collapsed. In February 1716, facing defeat, James and Lord Mar fled to France. After the rebellion was defeated, although there were some executions and forfeitures, George acted to moderate the Government's response, showed leniency, and spent the income from the forfeited estates on schools for Scotland and paying off part of the

Within a year of George's accession the Whigs won an overwhelming victory in the general election of 1715. Several members of the defeated Tory Party sympathised with the Jacobites, who sought to replace George with Anne's Catholic half-brother, James Francis Edward Stuart (called "James III and VIII" by his supporters and "the Pretender" by his opponents). Some disgruntled Tories sided with a Jacobite rebellion, which became known as "The Fifteen". James's supporters, led by Lord Mar, a Scottish nobleman who had previously served as a secretary of state, instigated rebellion in Scotland where support for Jacobitism was stronger than in England. "The Fifteen", however, was a dismal failure; Lord Mar's battle plans were poor, and James arrived late with too little money and too few arms. By the end of the year the rebellion had all but collapsed. In February 1716, facing defeat, James and Lord Mar fled to France. After the rebellion was defeated, although there were some executions and forfeitures, George acted to moderate the Government's response, showed leniency, and spent the income from the forfeited estates on schools for Scotland and paying off part of the

In Hanover, the King was an absolute monarch. All government expenditure above 50 thalers (between 12 and 13

In Hanover, the King was an absolute monarch. All government expenditure above 50 thalers (between 12 and 13

As requested by Walpole, George revived the Order of the Bath in 1725, which enabled Walpole to reward or gain political supporters by offering them the honour. Walpole became extremely powerful and was largely able to appoint ministers of his own choosing. Unlike his predecessor, Queen Anne, George rarely attended meetings of the cabinet; most of his communications were in private, and he only exercised substantial influence with respect to British foreign policy. With the aid of Lord Townshend, he arranged for the ratification by Great Britain, France and Prussia of the Treaty of Hanover, which was designed to counterbalance the Austro-Spanish Treaty of Vienna and protect British trade.

George, although increasingly reliant on Walpole, could still have replaced his ministers at will. Walpole was actually afraid of being removed from office towards the end of George I's reign, but such fears were put to an end when George died during his sixth trip to his native Hanover since his accession as king. He suffered a stroke on the road between Delden and Nordhorn on 9 June 1727, and was taken by carriage about 55 miles to the east, to the palace of his younger brother, Ernest Augustus, Prince-Bishop of Osnabrück, where he died two days after arrival in the early hours before dawn on 11 June 1727. George I was buried in the chapel of Leine Palace in Hanover, but his remains were moved to the chapel at Herrenhausen Gardens after World War II. Leine Palace was entirely burnt out as a result of Allied air raids and the King's remains, along with his parents', were moved to the 19th-century mausoleum of

As requested by Walpole, George revived the Order of the Bath in 1725, which enabled Walpole to reward or gain political supporters by offering them the honour. Walpole became extremely powerful and was largely able to appoint ministers of his own choosing. Unlike his predecessor, Queen Anne, George rarely attended meetings of the cabinet; most of his communications were in private, and he only exercised substantial influence with respect to British foreign policy. With the aid of Lord Townshend, he arranged for the ratification by Great Britain, France and Prussia of the Treaty of Hanover, which was designed to counterbalance the Austro-Spanish Treaty of Vienna and protect British trade.

George, although increasingly reliant on Walpole, could still have replaced his ministers at will. Walpole was actually afraid of being removed from office towards the end of George I's reign, but such fears were put to an end when George died during his sixth trip to his native Hanover since his accession as king. He suffered a stroke on the road between Delden and Nordhorn on 9 June 1727, and was taken by carriage about 55 miles to the east, to the palace of his younger brother, Ernest Augustus, Prince-Bishop of Osnabrück, where he died two days after arrival in the early hours before dawn on 11 June 1727. George I was buried in the chapel of Leine Palace in Hanover, but his remains were moved to the chapel at Herrenhausen Gardens after World War II. Leine Palace was entirely burnt out as a result of Allied air raids and the King's remains, along with his parents', were moved to the 19th-century mausoleum of  George was succeeded by his son, George Augustus, who took the throne as George II. It was widely assumed, even by Walpole for a time, that George II planned to remove Walpole from office but was dissuaded from doing so by his wife,

George was succeeded by his son, George Augustus, who took the throne as George II. It was widely assumed, even by Walpole for a time, that George II planned to remove Walpole from office but was dissuaded from doing so by his wife,

George was ridiculed by his British subjects;Hatton, p. 291. some of his contemporaries, such as Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, thought him unintelligent on the grounds that he was wooden in public. Though he was unpopular in Great Britain due to his supposed inability to speak English, such an inability may not have existed later in his reign as documents from that time show that he understood, spoke and wrote English. He certainly spoke fluent German and French, good Latin, and some Italian and Dutch. His treatment of his wife, Sophia Dorothea, became something of a scandal. His Lutheran faith, his overseeing both the Lutheran churches in Hanover and the Church of England, and the presence of Lutheran preachers in his court caused some consternation among his Anglican subjects.

The British perceived George as too German, and in the opinion of historian

George was ridiculed by his British subjects;Hatton, p. 291. some of his contemporaries, such as Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, thought him unintelligent on the grounds that he was wooden in public. Though he was unpopular in Great Britain due to his supposed inability to speak English, such an inability may not have existed later in his reign as documents from that time show that he understood, spoke and wrote English. He certainly spoke fluent German and French, good Latin, and some Italian and Dutch. His treatment of his wife, Sophia Dorothea, became something of a scandal. His Lutheran faith, his overseeing both the Lutheran churches in Hanover and the Church of England, and the presence of Lutheran preachers in his court caused some consternation among his Anglican subjects.

The British perceived George as too German, and in the opinion of historian

George I

at the official website of the British monarchy

George I

at the official website of the Royal Collection Trust

George I

at BBC History * , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:George 01 Of Great Britain 1660 births 1727 deaths 17th-century German people 18th-century German people 18th-century British people 18th-century Irish monarchs Prince-electors of Hanover Heirs presumptive to the British throne Monarchs of Great Britain Electoral Princes of Hanover Dukes of Bremen and Verden Dukes of Saxe-Lauenburg Princes of Calenberg Princes of Lüneburg English pretenders to the French throne House of Hanover Garter Knights appointed by William III Nobility from Hanover British monarchs buried abroad Burials at Berggarten Mausoleum, Herrenhausen (Hanover) Burials at the Leineschloss Osnabrück Military personnel from Hanover German army commanders in the War of the Spanish Succession

Electorate of Hanover

The Electorate of Hanover (german: Kurfürstentum Hannover or simply ''Kurhannover'') was an electorate of the Holy Roman Empire, located in northwestern Germany and taking its name from the capital city of Hanover. It was formally known as ...

within the Holy Roman Empire from 23 January 1698 until his death in 1727. He was the first British monarch

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the constitutional form of government by which a hereditary sovereign reigns as the head of state of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies (the Bailiwi ...

of the House of Hanover.

Born in Hanover to Ernest Augustus and Sophia of Hanover

Sophia of Hanover (born Princess Sophia of the Palatinate; 14 October 1630 – 8 June 1714) was the Electress of Hanover by marriage to Elector Ernest Augustus and later the heiress presumptive to the thrones of England and Scotland (later Grea ...

, George inherited the titles and lands of the Duchy of Brunswick-Lüneburg

The Duchy of Brunswick-Lüneburg (german: Herzogtum Braunschweig und Lüneburg), or more properly the Duchy of Brunswick and Lüneburg, was a historical duchy that existed from the late Middle Ages to the Late Modern era within the Holy Roman ...

from his father and uncles. In 1682, he married his cousin Sophia Dorothea of Celle, with whom he had two children; he also had three daughters with his mistress Melusine von der Schulenburg

Ehrengard Melusine von der Schulenburg, Duchess of Kendal, Duchess of Munster (25 December 166710 May 1743) was a longtime mistress to King George I of Great Britain.

Early life

She was born at Emden in the Duchy of Magdeburg. She was a daught ...

. George and Sophia Dorothea divorced in 1694. A succession of European wars expanded George's German domains during his lifetime; he was ratified as prince-elector of Hanover in 1708.

As the senior Protestant descendant of his great-grandfather James VI and I, George inherited the British throne following the deaths in 1714 of his mother, Sophia, and his second cousin Anne, Queen of Great Britain. Jacobites attempted, but failed, to depose George and replace him with James Francis Edward Stuart, Anne's Catholic half-brother. During George's reign the powers of the monarchy diminished, and Britain began a transition to the modern system of cabinet government led by a prime minister. Towards the end of his reign, actual political power was held by Robert Walpole

Robert Walpole, 1st Earl of Orford, (26 August 1676 – 18 March 1745; known between 1725 and 1742 as Sir Robert Walpole) was a British statesman and Whig politician who, as First Lord of the Treasury, Chancellor of the Exchequer, and Leader ...

, now recognised as Britain's first ''de facto'' prime minister.

George died of a stroke on a journey to his native Hanover, where he was buried. He is the most recent British monarch to be buried outside the United Kingdom.

Early life

George was born on 28 May 1660 in the city of Hanover in theDuchy of Brunswick-Lüneburg

The Duchy of Brunswick-Lüneburg (german: Herzogtum Braunschweig und Lüneburg), or more properly the Duchy of Brunswick and Lüneburg, was a historical duchy that existed from the late Middle Ages to the Late Modern era within the Holy Roman ...

in the Holy Roman Empire. He was the eldest son of Ernest Augustus, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg, and his wife, Sophia of the Palatinate. Sophia was the granddaughter of King James I of England, through her mother, Elizabeth Stuart, Queen of Bohemia.

For the first year of his life George was the only heir to the German territories of his father and three childless uncles. George's brother, Frederick Augustus, was born in 1661, and the two boys (known respectively by the family as "Görgen" and "Gustchen") were brought up together. In 1662 the family moved to Osnabrück when Ernest Augustus was appointed ruler of the Prince-Bishopric of Osnabrück, while his older brother George William ruled in Hanover. They lived at Iburg Castle outside the city until 1673 when they moved to the newly completed Schloss Osnabrück

''Schloss'' (; pl. ''Schlösser''), formerly written ''Schloß'', is the German term for a building similar to a château, palace, or manor house.

Related terms appear in several Germanic languages. In the Scandinavian languages, the cogna ...

. The parents were absent for almost a year (1664–1665) during a long convalescent holiday in Italy but Sophia corresponded regularly with her sons' governess and took a great interest in their upbringing, even more so upon her return. Sophia bore Ernest Augustus another four sons and a daughter. In her letters Sophia describes George as a responsible, conscientious child who set an example to his younger brothers and sisters.Hatton, p. 29.

By 1675 George's eldest uncle had died without issue, but his remaining two uncles had married, putting George's inheritance in jeopardy, for his uncles' estates might pass to their own sons, were they to have any, instead of to George. George's father took him hunting and riding and introduced him to military matters; mindful of his uncertain future, Ernest Augustus took the fifteen-year-old George on campaign in the Franco-Dutch War

The Franco-Dutch War, also known as the Dutch War (french: Guerre de Hollande; nl, Hollandse Oorlog), was fought between France and the Dutch Republic, supported by its allies the Holy Roman Empire, Spain, Brandenburg-Prussia and Denmark-Nor ...

with the deliberate purpose of testing and training his son in battle.

In 1679 another uncle died unexpectedly without sons, and Ernest Augustus became reigning Duke of Calenberg

The Calenberg is a hill in central Germany in the Leine depression near Pattensen in the municipality of Schulenburg. It lies 13 km west of the city of Hildesheim in south Lower Saxony on the edge of the Central Uplands. It is made from a ...

- Göttingen, with his capital at Hanover. George's surviving uncle, George William of Celle, had married his mistress in order to legitimise his only daughter, Sophia Dorothea, but looked unlikely to have any further children. Under Salic law

The Salic law ( or ; la, Lex salica), also called the was the ancient Frankish civil law code compiled around AD 500 by the first Frankish King, Clovis. The written text is in Latin and contains some of the earliest known instances of Old Du ...

, where inheritance of territory was restricted to the male line, the succession of George and his brothers to the territories of their father and uncle now seemed secure. In 1682 the family agreed to adopt the principle of primogeniture

Primogeniture ( ) is the right, by law or custom, of the firstborn legitimate child to inherit the parent's entire or main estate in preference to shared inheritance among all or some children, any illegitimate child or any collateral relativ ...

, meaning George would inherit all the territory and not have to share it with his brothers.

Marriage

In 1682, George married Sophia Dorothea of

In 1682, George married Sophia Dorothea of Celle

Celle () is a town and capital of the district of Celle, in Lower Saxony, Germany. The town is situated on the banks of the river Aller, a tributary of the Weser, and has a population of about 71,000. Celle is the southern gateway to the Lü ...

, the daughter of his uncle George William, thereby securing additional incomes that would have been outside Salic laws. This marriage of state was arranged primarily to ensure a healthy annual income, and assisted the eventual unification of Hanover and Celle. His mother at first opposed the marriage because she looked down on Sophia Dorothea's mother, Eleonore (who came from lower French nobility), and because she was concerned by Sophia Dorothea's legitimated status. She was eventually won over by the advantages inherent in the marriage.

In 1683, George and his brother Frederick Augustus served in the Great Turkish War

The Great Turkish War (german: Großer Türkenkrieg), also called the Wars of the Holy League ( tr, Kutsal İttifak Savaşları), was a series of conflicts between the Ottoman Empire and the Holy League consisting of the Holy Roman Empire, Pola ...

at the Battle of Vienna

The Battle of Vienna; pl, odsiecz wiedeńska, lit=Relief of Vienna or ''bitwa pod Wiedniem''; ota, Beç Ḳalʿası Muḥāṣarası, lit=siege of Beç; tr, İkinci Viyana Kuşatması, lit=second siege of Vienna took place at Kahlenberg Mou ...

, and Sophia Dorothea bore George a son, George Augustus Multiple people share the name George Augustus:

* George Baldwin Augustus, politician in Mississippi

* George Augustus Eliott, 1st Baron Heathfield

* George Augustus Sala

* George Augustus Selwyn, bishop.

* George II of Great Britain was earlie ...

. The following year, Frederick Augustus was informed of the adoption of primogeniture, meaning he would no longer receive part of his father's territory as he had expected. This led to a breach between Frederick Augustus and his father, and between the brothers, that lasted until his death in battle in 1690. With the imminent formation of a single Hanoverian state, and the Hanoverians' continuing contributions to the Empire's wars, Ernest Augustus was made an Elector of the Holy Roman Empire in 1692. George's prospects were now better than ever as the sole heir to his father's electorate and his uncle's duchy.

Sophia Dorothea had a second child, a daughter named after her, in 1687, but there were no other pregnancies. The couple became estranged—George preferred the company of his mistress, Melusine von der Schulenburg

Ehrengard Melusine von der Schulenburg, Duchess of Kendal, Duchess of Munster (25 December 166710 May 1743) was a longtime mistress to King George I of Great Britain.

Early life

She was born at Emden in the Duchy of Magdeburg. She was a daught ...

, and Sophia Dorothea had her own romance with the Swedish Count Philip Christoph von Königsmarck. Threatened with the scandal of an elopement, the Hanoverian court, including George's brothers and mother, urged the lovers to desist, but to no avail. According to diplomatic sources from Hanover's enemies, in July 1694, the Swedish count was killed, possibly with George's connivance, and his body thrown into the river Leine weighted with stones. The murder was claimed to have been committed by four of Ernest Augustus's courtiers, one of whom, Don Nicolò Montalbano, was paid the enormous sum of 150,000 thaler

A thaler (; also taler, from german: Taler) is one of the large silver coins minted in the states and territories of the Holy Roman Empire and the Habsburg monarchy during the Early Modern period. A ''thaler'' size silver coin has a diameter of ...

s, about one hundred times the annual salary of the highest-paid minister.Hatton, pp. 51–61. Later rumours supposed that Königsmarck was hacked to pieces and buried beneath the Hanover palace floorboards. However, sources in Hanover itself, including Sophia, denied any knowledge of Königsmarck's whereabouts.

George's marriage to Sophia Dorothea was dissolved, not on the grounds that either of them had committed adultery, but on the grounds that Sophia Dorothea had abandoned her husband. With her father's agreement, George had Sophia Dorothea imprisoned in Ahlden House in her native Celle

Celle () is a town and capital of the district of Celle, in Lower Saxony, Germany. The town is situated on the banks of the river Aller, a tributary of the Weser, and has a population of about 71,000. Celle is the southern gateway to the Lü ...

, where she stayed until she died more than thirty years later. She was denied access to her children and father, forbidden to remarry and only allowed to walk unaccompanied within the mansion courtyard. She was, however, endowed with an income, establishment, and servants, and allowed to ride in a carriage outside her castle under supervision. Melusine von der Schulenburg acted as George's hostess openly from 1698 until his death, and they had three daughters together, born in 1692, 1693 and 1701.

Electoral reign

Ernest Augustus died on 23 January 1698, leaving all of his territories to George with the exception of the Prince-Bishopric of Osnabrück, an office he had held since 1661. George thus became Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg (also known as Hanover, after its capital) as well as Archbannerbearer and a Prince-Elector of the Holy Roman Empire. His court in Hanover was graced by many cultural icons such as the mathematician and philosopher Gottfried Leibniz and the composers

Ernest Augustus died on 23 January 1698, leaving all of his territories to George with the exception of the Prince-Bishopric of Osnabrück, an office he had held since 1661. George thus became Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg (also known as Hanover, after its capital) as well as Archbannerbearer and a Prince-Elector of the Holy Roman Empire. His court in Hanover was graced by many cultural icons such as the mathematician and philosopher Gottfried Leibniz and the composers George Frideric Händel

George Frideric (or Frederick) Handel (; baptised , ; 23 February 1685 – 14 April 1759) was a German-British Baroque composer well known for his operas, oratorios, anthems, concerti grossi, and organ concertos. Handel received his trainin ...

and Agostino Steffani

Agostino Steffani (25 July 165412 February 1728) was an Italian ecclesiastic, diplomat and composer.

Biography

Steffani was born at Castelfranco Veneto on 25 July 1654. As a boy he was admitted as a chorister at San Marco, Venice. In 1667, ...

.

Shortly after George's accession to his paternal duchy, Prince William, Duke of Gloucester, who was second-in-line to the English and Scottish thrones, died. By the terms of the English Act of Settlement 1701

The Act of Settlement is an Act of the Parliament of England that settled the succession to the English and Irish crowns to only Protestants, which passed in 1701. More specifically, anyone who became a Roman Catholic, or who married one, bec ...

, George's mother, Sophia, was designated as the heir to the English throne if the then reigning monarch, William III William III or William the Third may refer to:

Kings

* William III of Sicily (c. 1186–c. 1198)

* William III of England and Ireland or William III of Orange or William II of Scotland (1650–1702)

* William III of the Netherlands and Luxembourg ...

, and his sister-in-law, Anne, died without surviving issue. The succession

Succession is the act or process of following in order or sequence.

Governance and politics

*Order of succession, in politics, the ascension to power by one ruler, official, or monarch after the death, resignation, or removal from office of ...

was so designed because Sophia was the closest Protestant relative of the British royal family. Fifty-six Catholics with superior hereditary claims were bypassed. The likelihood of any of them converting to Protestantism for the sake of the succession was remote; some had already refused.

In August 1701, George was invested with the Order of the Garter

The Most Noble Order of the Garter is an order of chivalry founded by Edward III of England in 1348. It is the most senior order of knighthood in the British honours system, outranked in precedence only by the Victoria Cross and the George C ...

and, within six weeks, the nearest Catholic claimant to the thrones, the former king James II James II may refer to:

* James II of Avesnes (died c. 1205), knight of the Fourth Crusade

* James II of Majorca (died 1311), Lord of Montpellier

* James II of Aragon (1267–1327), King of Sicily

* James II, Count of La Marche (1370–1438), King C ...

, died. William III died the following March and was succeeded by Anne. Sophia became heiress presumptive to the new Queen of England. Sophia was in her seventy-first year, thirty-five years older than Anne, but she was very fit and healthy and invested time and energy in securing the succession either for herself or for her son. However, it was George who understood the complexities of English politics and constitutional law, which required further acts in 1705 to naturalise Sophia and her heirs as English subjects, and to detail arrangements for the transfer of power through a Regency Council. In the same year, George's surviving uncle died and he inherited further German dominions: the Principality of Lüneburg- Grubenhagen, centred at Celle

Celle () is a town and capital of the district of Celle, in Lower Saxony, Germany. The town is situated on the banks of the river Aller, a tributary of the Weser, and has a population of about 71,000. Celle is the southern gateway to the Lü ...

.

Shortly after George's accession in Hanover, the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1714) broke out. At issue was the right of

Shortly after George's accession in Hanover, the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1714) broke out. At issue was the right of Philip

Philip, also Phillip, is a male given name, derived from the Greek (''Philippos'', lit. "horse-loving" or "fond of horses"), from a compound of (''philos'', "dear", "loved", "loving") and (''hippos'', "horse"). Prominent Philips who popularize ...

, the grandson of King Louis XIV of France, to succeed to the Spanish throne under the terms of King Charles II of Spain's will

Will may refer to:

Common meanings

* Will and testament, instructions for the disposition of one's property after death

* Will (philosophy), or willpower

* Will (sociology)

* Will, volition (psychology)

* Will, a modal verb - see Shall and will

...

. The Holy Roman Empire, the United Dutch Provinces

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, also known as the (Seven) United Provinces, officially as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands (Dutch: ''Republiek der Zeven Verenigde Nederlanden''), and commonly referred to in historiography ...

, England, Hanover and many other German states opposed Philip's right to succeed because they feared that the French House of Bourbon

The House of Bourbon (, also ; ) is a European dynasty of French origin, a branch of the Capetian dynasty, the royal House of France. Bourbon kings first ruled France and Navarre in the 16th century. By the 18th century, members of the Spanis ...

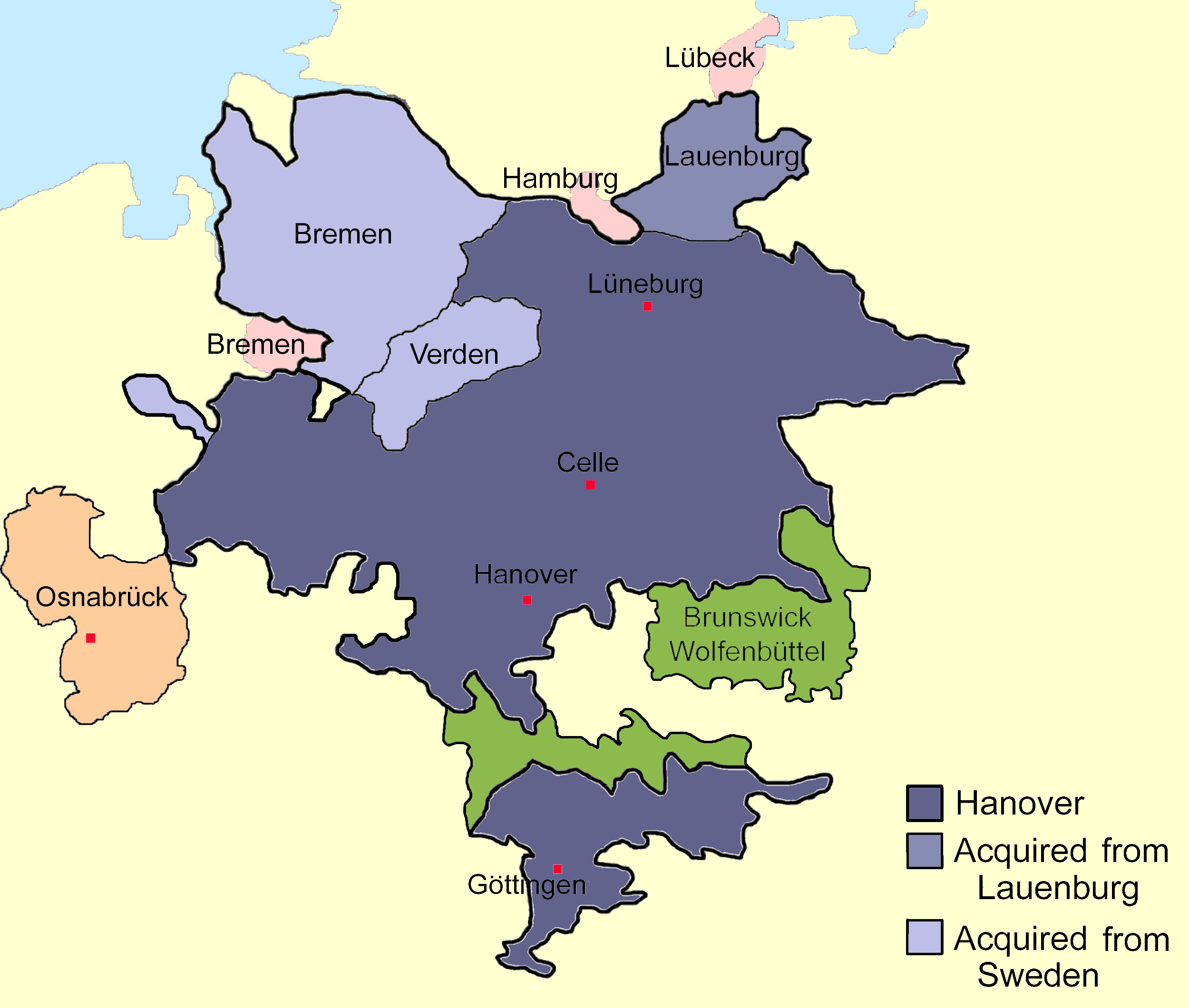

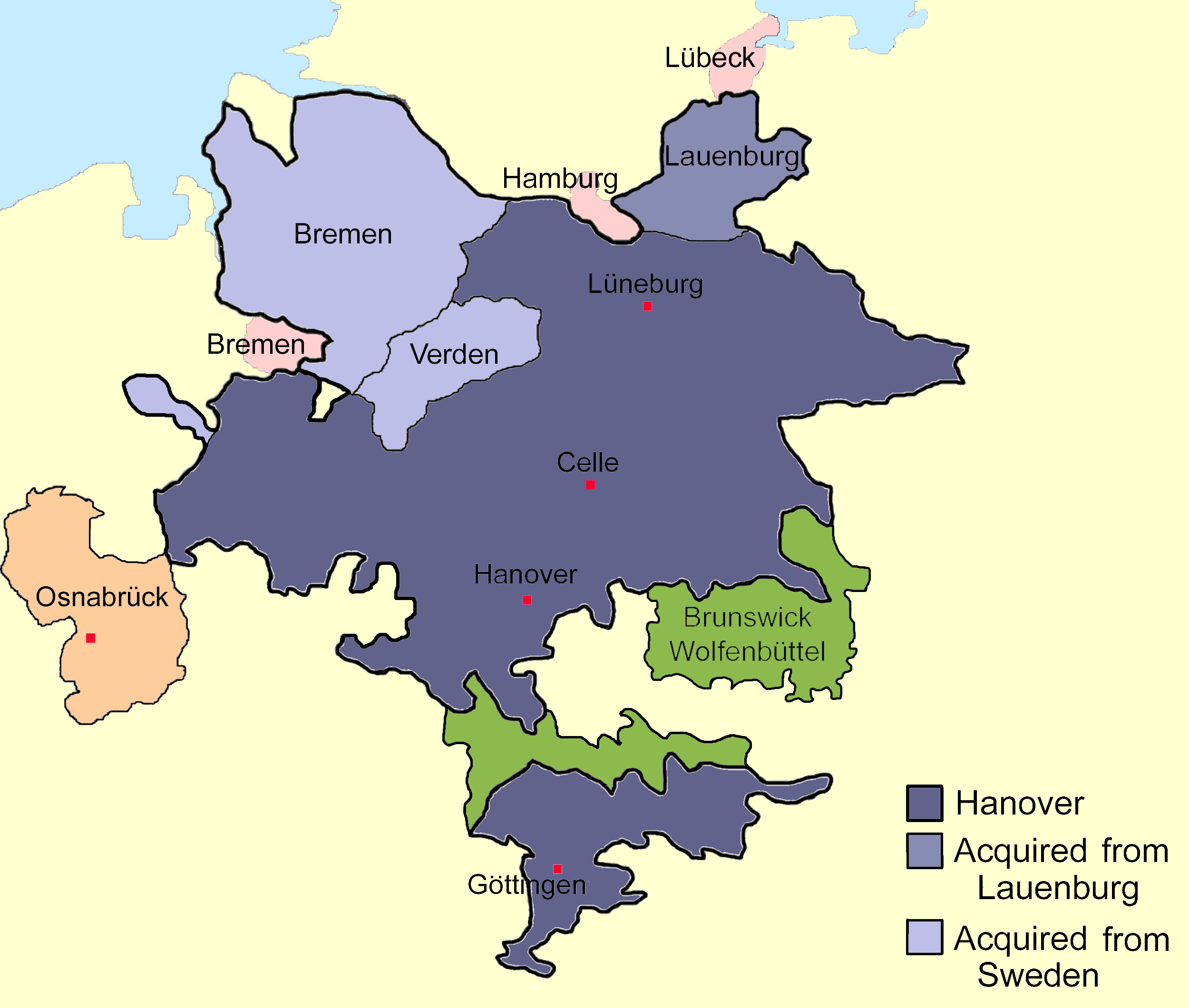

would become too powerful if it also controlled Spain. As part of the war effort, George invaded his neighbouring state, Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, which was pro-French, writing out some of the battle orders himself. The invasion succeeded with few lives lost. As a reward, the prior Hanoverian annexation of the Duchy of Saxe-Lauenburg by George's uncle was recognised by the British and Dutch.

In 1706, the Elector of Bavaria was deprived of his offices and titles for siding with Louis against the Empire. The following year, George was invested as an Imperial Field Marshal with command of the imperial army stationed along the Rhine. His tenure was not altogether successful, partly because he was deceived by his ally, the Duke of Marlborough, into a diversionary attack, and partly because Emperor Joseph I appropriated the funds necessary for George's campaign for his own use. Despite this, the German princes thought he had acquitted himself well. In 1708, they formally confirmed George's position as a Prince-Elector in recognition of, or because of, his service. George did not hold Marlborough's actions against him; he understood they were part of a plan to lure French forces away from the main attack.

In 1709, George resigned as field marshal, never to go on active service again. In 1710, he was granted the dignity of Arch-Treasurer of the Empire, an office formerly held by the Elector Palatine; the absence of the Elector of Bavaria allowed a reshuffling of offices. The emperor's death in 1711 threatened to destroy the balance of power in the opposite direction, so the war ended in 1713 with the ratification of the Treaty of Utrecht. Philip was allowed to succeed to the Spanish throne but removed from the French line of succession, and the Elector of Bavaria was restored.

Accession in Great Britain and Ireland

Though both England and Scotland recognised Anne as their queen, only the Parliament of England had settled on Sophia, Electress of Hanover, as the heir presumptive. The Parliament of Scotland (the Estates) had not formally settled the succession question for the Scottish throne. In 1703, the Estates passed a bill declaring that their selection for Queen Anne's successor would not be the same individual as the successor to the English throne, unless England granted full freedom of trade to Scottish merchants in England and its colonies. At first Royal Assent was withheld, but the following year Anne capitulated to the wishes of the Estates and assent was granted to the bill, which became the Act of Security 1704. In response the English Parliament passed the Alien Act 1705, which threatened to restrict Anglo-Scottish trade and cripple the Scottish economy if the Estates did not agree to the Hanoverian succession. Eventually, in 1707, both Parliaments agreed on a Treaty of Union, which united England and Scotland into a single political entity, the Kingdom of Great Britain, and established the rules of succession as laid down by the

Though both England and Scotland recognised Anne as their queen, only the Parliament of England had settled on Sophia, Electress of Hanover, as the heir presumptive. The Parliament of Scotland (the Estates) had not formally settled the succession question for the Scottish throne. In 1703, the Estates passed a bill declaring that their selection for Queen Anne's successor would not be the same individual as the successor to the English throne, unless England granted full freedom of trade to Scottish merchants in England and its colonies. At first Royal Assent was withheld, but the following year Anne capitulated to the wishes of the Estates and assent was granted to the bill, which became the Act of Security 1704. In response the English Parliament passed the Alien Act 1705, which threatened to restrict Anglo-Scottish trade and cripple the Scottish economy if the Estates did not agree to the Hanoverian succession. Eventually, in 1707, both Parliaments agreed on a Treaty of Union, which united England and Scotland into a single political entity, the Kingdom of Great Britain, and established the rules of succession as laid down by the Act of Settlement 1701

The Act of Settlement is an Act of the Parliament of England that settled the succession to the English and Irish crowns to only Protestants, which passed in 1701. More specifically, anyone who became a Roman Catholic, or who married one, bec ...

. The union created the largest free trade area in 18th-century Europe.

Whig politicians believed Parliament had the right to determine the succession, and to bestow it on the nearest Protestant relative of the Queen, while many Tories were more inclined to believe in the hereditary right of the Catholic Stuarts

The House of Stuart, originally spelt Stewart, was a royal house of Scotland, England, Ireland and later Great Britain. The family name comes from the office of High Steward of Scotland, which had been held by the family progenitor Walter fi ...

, who were nearer relations. In 1710, George announced that he would succeed in Britain by hereditary right, as the right had been removed from the Stuarts, and he retained it. "This declaration was meant to scotch any Whig interpretation that parliament had given him the kingdom nd... convince the Tories that he was no usurper."

George's mother, the Electress Sophia, died on 28 May 1714 at the age of 83. She had collapsed in the gardens at Herrenhausen after rushing to shelter from a shower of rain. George was now Queen Anne's heir presumptive. He swiftly revised the membership of the Regency Council that would take power after Anne's death, as it was known that Anne's health was failing and politicians in Britain were jostling for power. She suffered a stroke, which left her unable to speak, and died on 1 August 1714. The list of regents was opened, the members sworn in, and George was proclaimed King of Great Britain and King of Ireland. Partly due to contrary winds, which kept him in The Hague awaiting passage, he did not arrive in Britain until 18 September. George was crowned at Westminster Abbey on 20 October. His coronation was accompanied by rioting in over twenty towns in England.

George mainly lived in Great Britain after 1714, though he visited his home in Hanover in 1716, 1719, 1720, 1723 and 1725. In total, George spent about one fifth of his reign as king in Germany.Gibbs (2004). A clause in the Act of Settlement that forbade the British monarch from leaving the country without Parliament's permission was unanimously repealed in 1716. During all but the first of the King's absences, power was vested in a Regency Council rather than in his son, George Augustus, Prince of Wales.

Wars and rebellions

Within a year of George's accession the Whigs won an overwhelming victory in the general election of 1715. Several members of the defeated Tory Party sympathised with the Jacobites, who sought to replace George with Anne's Catholic half-brother, James Francis Edward Stuart (called "James III and VIII" by his supporters and "the Pretender" by his opponents). Some disgruntled Tories sided with a Jacobite rebellion, which became known as "The Fifteen". James's supporters, led by Lord Mar, a Scottish nobleman who had previously served as a secretary of state, instigated rebellion in Scotland where support for Jacobitism was stronger than in England. "The Fifteen", however, was a dismal failure; Lord Mar's battle plans were poor, and James arrived late with too little money and too few arms. By the end of the year the rebellion had all but collapsed. In February 1716, facing defeat, James and Lord Mar fled to France. After the rebellion was defeated, although there were some executions and forfeitures, George acted to moderate the Government's response, showed leniency, and spent the income from the forfeited estates on schools for Scotland and paying off part of the

Within a year of George's accession the Whigs won an overwhelming victory in the general election of 1715. Several members of the defeated Tory Party sympathised with the Jacobites, who sought to replace George with Anne's Catholic half-brother, James Francis Edward Stuart (called "James III and VIII" by his supporters and "the Pretender" by his opponents). Some disgruntled Tories sided with a Jacobite rebellion, which became known as "The Fifteen". James's supporters, led by Lord Mar, a Scottish nobleman who had previously served as a secretary of state, instigated rebellion in Scotland where support for Jacobitism was stronger than in England. "The Fifteen", however, was a dismal failure; Lord Mar's battle plans were poor, and James arrived late with too little money and too few arms. By the end of the year the rebellion had all but collapsed. In February 1716, facing defeat, James and Lord Mar fled to France. After the rebellion was defeated, although there were some executions and forfeitures, George acted to moderate the Government's response, showed leniency, and spent the income from the forfeited estates on schools for Scotland and paying off part of the national debt

A country's gross government debt (also called public debt, or sovereign debt) is the financial liabilities of the government sector. Changes in government debt over time reflect primarily borrowing due to past government deficits. A deficit oc ...

.

George's distrust of the Tories aided the passing of power to the Whigs. Whig dominance grew to be so great under George that the Tories did not return to power for another half-century. After the election, the Whig-dominated Parliament passed the Septennial Act 1715

The Septennial Act 1715 (1 Geo 1 St 2 c 38), sometimes called the Septennial Act 1716, was an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain. It was passed in May 1716. It increased the maximum length of a parliament (and hence the maximum period between ...

, which extended the maximum duration of Parliament to seven years (although it could be dissolved earlier by the Sovereign). Thus Whigs already in power could remain in such a position for a greater period of time.

After his accession in Great Britain, George's relationship with his son (which had always been poor) worsened. Prince George Augustus encouraged opposition to his father's policies, including measures designed to increase religious freedom in Britain and expand Hanover's German territories at Sweden's expense. In 1717, the birth of a grandson led to a major quarrel between George and the Prince of Wales. The King, supposedly following custom, appointed the Lord Chamberlain ( Thomas Pelham-Holles, 1st Duke of Newcastle) as one of the baptismal sponsors of the child. The King was angered when the Prince of Wales, disliking Newcastle, verbally insulted the Duke at the christening, which the Duke misunderstood as a challenge to a duel. The Prince was told to leave the royal residence, St. James's Palace

St James's Palace is the most senior royal palace in London, the capital of the United Kingdom. The palace gives its name to the Court of St James's, which is the monarch's royal court, and is located in the City of Westminster in London. Alt ...

. The Prince's new home, Leicester House, became a meeting place for the King's political opponents.Dickinson, p. 49. The King and his son were later reconciled at the insistence of Robert Walpole

Robert Walpole, 1st Earl of Orford, (26 August 1676 – 18 March 1745; known between 1725 and 1742 as Sir Robert Walpole) was a British statesman and Whig politician who, as First Lord of the Treasury, Chancellor of the Exchequer, and Leader ...

and the desire of the Princess of Wales

Princess of Wales (Welsh: ''Tywysoges Cymru'') is a courtesy title used since the 14th century by the wife of the heir apparent to the English and later British throne. The current title-holder is Catherine (née Middleton).

The title was firs ...

, who had moved out with her husband but missed her children, who had been left in the King's care. Nevertheless, father and son were never again on cordial terms.

George was active in directing British foreign policy during his early reign. In 1717, he contributed to the creation of the Triple Alliance Triple Alliance may refer to:

* Aztec Triple Alliance (1428–1521), Tenochtitlan, Texcoco, and Tlacopan and in central Mexico

* Triple Alliance (1596), England, France, and the Dutch Republic to counter Spain

* Triple Alliance (1668), England, the ...

, an anti-Spanish league composed of Great Britain, France and the Dutch Republic. In 1718, the Holy Roman Empire was added to the body, which became known as the Quadruple Alliance. The subsequent War of the Quadruple Alliance involved the same issue as the War of the Spanish Succession. The 1713 Treaty of Utrecht had recognised the grandson of Louis XIV of France, Philip V Philip V may refer to:

* Philip V of Macedon (221–179 BC)

* Philip V of France (1293–1322)

* Philip II of Spain

Philip II) in Spain, while in Portugal and his Italian kingdoms he ruled as Philip I ( pt, Filipe I). (21 May 152713 September ...

, as king of Spain on the condition that he gave up his rights to succeed to the French throne. But upon Louis XIV's 1715 death, Philip sought to overturn the treaty.

Spain supported a Jacobite-led invasion of Scotland in 1719, but stormy seas allowed only about three hundred Spanish troops to reach Scotland. A base was established at Eilean Donan Castle on the west Scottish coast in April, only to be destroyed by British ships a month later. Jacobite attempts to recruit Scottish clansmen yielded a fighting force of only about a thousand men. The Jacobites were poorly equipped and were easily defeated by British artillery at the Battle of Glen Shiel. The clansmen dispersed into the Highlands, and the Spaniards surrendered. The invasion never posed any serious threat to George's government. With the French now fighting against him, Philip's armies fared poorly. As a result, the Spanish and French thrones remained separate. Simultaneously, Hanover gained from the resolution of the Great Northern War, which had been caused by rivalry between Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden,The United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names states that the country's formal name is the Kingdom of SwedenUNGEGN World Geographical Names, Sweden./ref> is a Nordic country located on ...

and Russia for control of the Baltic

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from 10 ...

. The Swedish territories of Bremen and Verden were ceded to Hanover in 1719, with Hanover paying Sweden monetary compensation for the loss of territory.

Ministries

In Hanover, the King was an absolute monarch. All government expenditure above 50 thalers (between 12 and 13

In Hanover, the King was an absolute monarch. All government expenditure above 50 thalers (between 12 and 13 British pound

Sterling (abbreviation: stg; Other spelling styles, such as STG and Stg, are also seen. ISO code: GBP) is the currency of the United Kingdom and nine of its associated territories. The pound ( sign: £) is the main unit of sterling, and t ...

s), and the appointment of all army officers, all ministers, and even government officials above the level of copyist, was in his personal control. By contrast in Great Britain, George had to govern through Parliament.

In 1715 when the Whigs came to power, George's chief ministers included Robert Walpole

Robert Walpole, 1st Earl of Orford, (26 August 1676 – 18 March 1745; known between 1725 and 1742 as Sir Robert Walpole) was a British statesman and Whig politician who, as First Lord of the Treasury, Chancellor of the Exchequer, and Leader ...

, Lord Townshend

Marquess Townshend is a title in the Peerage of Great Britain held by the Townshend family of Raynham Hall in Norfolk. The title was created in 1787 for George Townshend, 1st Marquess Townshend, George Townshend, 4th Viscount Townshend.

Histor ...

(Walpole's brother-in-law), Lord Stanhope and Lord Sunderland

Duke of Marlborough (pronounced ) is a title in the Peerage of England. It was created by Queen Anne in 1702 for John Churchill, 1st Earl of Marlborough (1650–1722), the noted military leader. In historical texts, unqualified use of the tit ...

. In 1717 Townshend was dismissed, and Walpole resigned from the Cabinet over disagreements with their colleagues; Stanhope became supreme in foreign affairs, and Sunderland the same in domestic matters.

Lord Sunderland's power began to wane in 1719. He introduced a Peerage Bill that attempted to limit the size of the House of Lords by restricting new creations. The measure would have solidified Sunderland's control of the House by preventing the creation of opposition peers, but it was defeated after Walpole led the opposition to the bill by delivering what was considered "the most brilliant speech of his career".Hatton, pp. 244–246. Walpole and Townshend were reappointed as ministers the following year and a new, supposedly unified, Whig government formed.

Greater problems arose over financial speculation and the management of the national debt. Certain government bonds could not be redeemed without the consent of the bondholder and had been issued when interest rates were high; consequently each bond represented a long-term drain on public finances, as bonds were hardly ever redeemed. In 1719, the South Sea Company proposed to take over £31 million (three fifths) of the British national debt by exchanging government securities for stock in the company. The Company bribed Lord Sunderland, George's mistress Melusine von der Schulenburg, and Lord Stanhope's cousin, Secretary of the Treasury Charles Stanhope, to support their plan. The Company enticed bondholders to convert their high-interest, irredeemable bonds to low-interest, easily tradeable stocks by offering apparently preferential financial gains. Company prices rose rapidly; the shares had cost £128 on 1 January 1720, but were valued at £500 when the conversion scheme opened in May. On 24 June the price reached a peak of £1,050. The company's success led to the speculative flotation of other companies, some of a bogus nature, and the Government, in an attempt to suppress these schemes and with the support of the company, passed the Bubble Act. With the rise in the market now halted, uncontrolled selling began in August, which caused the stock to plummet to £150 by the end of September. Many individuals—including aristocrats—lost vast sums and some were completely ruined. George, who had been in Hanover since June, returned to London in November—sooner than he wanted or was usual—at the request of the ministry.

The economic crisis, known as the South Sea Bubble, made George and his ministers extremely unpopular. In 1721, Lord Stanhope, though personally innocent, collapsed and died after a stressful debate in the House of Lords, and Lord Sunderland resigned from public office.

Sunderland, however, retained a degree of personal influence with George until his sudden death in 1722 allowed the rise of Robert Walpole. Walpole became ''de facto'' Prime Minister, although the title was not formally applied to him (officially, he was First Lord of the Treasury and Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the Exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and head of His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, the Chancellor is ...

). His management of the South Sea crisis, by rescheduling the debts and arranging some compensation, helped the return to financial stability. Through Walpole's skilful management of Parliament, George managed to avoid direct implication in the company's fraudulent actions. Claims that George had received free stock as a bribe are not supported by evidence; indeed receipts in the Royal Archives show that he paid for his subscriptions and that he lost money in the crash.

Later years

As requested by Walpole, George revived the Order of the Bath in 1725, which enabled Walpole to reward or gain political supporters by offering them the honour. Walpole became extremely powerful and was largely able to appoint ministers of his own choosing. Unlike his predecessor, Queen Anne, George rarely attended meetings of the cabinet; most of his communications were in private, and he only exercised substantial influence with respect to British foreign policy. With the aid of Lord Townshend, he arranged for the ratification by Great Britain, France and Prussia of the Treaty of Hanover, which was designed to counterbalance the Austro-Spanish Treaty of Vienna and protect British trade.

George, although increasingly reliant on Walpole, could still have replaced his ministers at will. Walpole was actually afraid of being removed from office towards the end of George I's reign, but such fears were put to an end when George died during his sixth trip to his native Hanover since his accession as king. He suffered a stroke on the road between Delden and Nordhorn on 9 June 1727, and was taken by carriage about 55 miles to the east, to the palace of his younger brother, Ernest Augustus, Prince-Bishop of Osnabrück, where he died two days after arrival in the early hours before dawn on 11 June 1727. George I was buried in the chapel of Leine Palace in Hanover, but his remains were moved to the chapel at Herrenhausen Gardens after World War II. Leine Palace was entirely burnt out as a result of Allied air raids and the King's remains, along with his parents', were moved to the 19th-century mausoleum of

As requested by Walpole, George revived the Order of the Bath in 1725, which enabled Walpole to reward or gain political supporters by offering them the honour. Walpole became extremely powerful and was largely able to appoint ministers of his own choosing. Unlike his predecessor, Queen Anne, George rarely attended meetings of the cabinet; most of his communications were in private, and he only exercised substantial influence with respect to British foreign policy. With the aid of Lord Townshend, he arranged for the ratification by Great Britain, France and Prussia of the Treaty of Hanover, which was designed to counterbalance the Austro-Spanish Treaty of Vienna and protect British trade.

George, although increasingly reliant on Walpole, could still have replaced his ministers at will. Walpole was actually afraid of being removed from office towards the end of George I's reign, but such fears were put to an end when George died during his sixth trip to his native Hanover since his accession as king. He suffered a stroke on the road between Delden and Nordhorn on 9 June 1727, and was taken by carriage about 55 miles to the east, to the palace of his younger brother, Ernest Augustus, Prince-Bishop of Osnabrück, where he died two days after arrival in the early hours before dawn on 11 June 1727. George I was buried in the chapel of Leine Palace in Hanover, but his remains were moved to the chapel at Herrenhausen Gardens after World War II. Leine Palace was entirely burnt out as a result of Allied air raids and the King's remains, along with his parents', were moved to the 19th-century mausoleum of King Ernest Augustus

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen, which title is also given to the consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contemporary indigenous peoples, the tit ...

in the Berggarten.

George was succeeded by his son, George Augustus, who took the throne as George II. It was widely assumed, even by Walpole for a time, that George II planned to remove Walpole from office but was dissuaded from doing so by his wife,

George was succeeded by his son, George Augustus, who took the throne as George II. It was widely assumed, even by Walpole for a time, that George II planned to remove Walpole from office but was dissuaded from doing so by his wife, Caroline of Ansbach

, father = John Frederick, Margrave of Brandenburg-Ansbach

, mother = Princess Eleonore Erdmuthe of Saxe-Eisenach

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Ansbach, Principality of Ansbach, Holy Roman Empire

, death_date =

, death_place = St James's Pala ...

. However, Walpole commanded a substantial majority in Parliament and George II had little choice but to retain him or risk ministerial instability.

Legacy

George was ridiculed by his British subjects;Hatton, p. 291. some of his contemporaries, such as Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, thought him unintelligent on the grounds that he was wooden in public. Though he was unpopular in Great Britain due to his supposed inability to speak English, such an inability may not have existed later in his reign as documents from that time show that he understood, spoke and wrote English. He certainly spoke fluent German and French, good Latin, and some Italian and Dutch. His treatment of his wife, Sophia Dorothea, became something of a scandal. His Lutheran faith, his overseeing both the Lutheran churches in Hanover and the Church of England, and the presence of Lutheran preachers in his court caused some consternation among his Anglican subjects.

The British perceived George as too German, and in the opinion of historian

George was ridiculed by his British subjects;Hatton, p. 291. some of his contemporaries, such as Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, thought him unintelligent on the grounds that he was wooden in public. Though he was unpopular in Great Britain due to his supposed inability to speak English, such an inability may not have existed later in his reign as documents from that time show that he understood, spoke and wrote English. He certainly spoke fluent German and French, good Latin, and some Italian and Dutch. His treatment of his wife, Sophia Dorothea, became something of a scandal. His Lutheran faith, his overseeing both the Lutheran churches in Hanover and the Church of England, and the presence of Lutheran preachers in his court caused some consternation among his Anglican subjects.

The British perceived George as too German, and in the opinion of historian Ragnhild Hatton

Ragnhild Marie Hatton (born 10 January 1913 in Bergen, Norway – died 16 May 1995 in London) was professor of International History at the London School of Economics. As the author of her obituary declared, she was "for a generation Britai ...

, wrongly assumed that he had a succession of German mistresses.Hatton, pp. 132–136. However, in mainland Europe, he was seen as a progressive ruler supportive of the Enlightenment who permitted his critics to publish without risk of severe censorship, and provided sanctuary to Voltaire when the philosopher was exiled from Paris in 1726. European and British sources agree that George was reserved, temperate and financially prudent; he disliked being in the public light at social events, avoided the royal box at the opera and often travelled incognito to the homes of friends to play cards. Despite some unpopularity, the Protestant George I was seen by most of his subjects as a better alternative to the Roman Catholic pretender James. William Makepeace Thackeray indicates such ambivalent feelings as he wrote:

Writers of the nineteenth century, such as Thackeray, Walter Scott and Lord Mahon

Philip Henry Stanhope, 5th Earl Stanhope, (30 January 180524 December 1875), styled Viscount Mahon between 1816 and 1855, was an English antiquarian and Tory politician. He held political office under Sir Robert Peel in the 1830s and 1840s but ...

, were reliant on biased first-hand accounts published in the previous century such as Lord Hervey's memoirs, and looked back on the Jacobite cause with romantic, even sympathetic, eyes. They in turn, influenced British authors of the first half of the twentieth century such as G. K. Chesterton

Gilbert Keith Chesterton (29 May 1874 – 14 June 1936) was an English writer, philosopher, Christian apologist, and literary and art critic. He has been referred to as the "prince of paradox". Of his writing style, ''Time'' observed: "Wh ...

, who introduced further anti-German and anti-Protestant bias into the interpretation of George's reign. However, in the wake of World War II continental European archives were opened to historians of the later twentieth century and nationalistic anti-German feeling subsided. George's life and reign were re-explored by scholars such as Beattie and Hatton, and his character, abilities and motives re-assessed in a more generous light. John H. Plumb noted that:

Yet the character of George I remains elusive; he was in turn genial and affectionate in private letters to his daughter, and then dull and awkward in public. Perhaps his own mother summed him up when "explaining to those who regarded him as cold and overserious that he could be jolly, that he took things to heart, that he felt deeply and sincerely and was more sensitive than he cared to show." Whatever his true character, he ascended a precarious throne, and either by political wisdom and guile, or through accident and indifference, he left it secure in the hands of the Hanoverians and of Parliament.

Arms

As king, his arms were: Quarterly, I,Gules

In heraldry, gules () is the tincture with the colour red. It is one of the class of five dark tinctures called "colours", the others being azure (blue), sable (black), vert (green) and purpure (purple).

In engraving, it is sometimes depict ...

three lions passant guardant in pale

Pale may refer to:

Jurisdictions

* Medieval areas of English conquest:

** Pale of Calais, in France (1360–1558)

** The Pale, or the English Pale, in Ireland

*Pale of Settlement, area of permitted Jewish settlement, western Russian Empire (179 ...

Or ( for England) impaling Or a lion rampant within a tressure flory-counter-flory Gules ( for Scotland); II, Azure

Azure may refer to:

Colour

* Azure (color), a hue of blue

** Azure (heraldry)

** Shades of azure, shades and variations

Arts and media

* ''Azure'' (Art Farmer and Fritz Pauer album), 1987

* Azure (Gary Peacock and Marilyn Crispell album), 2013

...

three fleurs-de-lis Or (for France); III, Azure a harp Or stringed Argent ( for Ireland); IV, tierced per pale and per chevron (for Hanover), I Gules two lions passant guardant Or (for Brunswick), II Or a semy of hearts Gules a lion rampant Azure (for Lüneburg), III Gules a horse courant

Courant may refer to:

* '' Hexham Courant'', a weekly newspaper in Northumberland, England

* ''The New-England Courant'', an American newspaper, founded in Boston in 1721

* ''Hartford Courant'', a newspaper in the United States, founded in 1764

*C ...

Argent ( for Westphalia), overall an escutcheon Gules charged with the crown of Charlemagne Or (for the dignity of Archtreasurer of the Holy Roman Empire).Williams, p. 12.; ;

Issue and mistresses

Issue

Mistresses

In addition to Melusine von der Schulenburg, three other women were said to be George's mistresses: # Leonora von Meyseburg-Züschen, widow of a Chamberlain at the court of Hanover, and secondly married toLieutenant-General

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the ...

de Weyhe. Leonore was the sister of Clara Elisabeth von Meyseburg-Züschen, Countess von Platen, who had been the mistress of George I's father, Ernest Augustus, Elector of Hanover.

# Sophia Charlotte von Platen, later Countess of Darlington (1673 – 20 April 1725), shown by Ragnhild Hatton

Ragnhild Marie Hatton (born 10 January 1913 in Bergen, Norway – died 16 May 1995 in London) was professor of International History at the London School of Economics. As the author of her obituary declared, she was "for a generation Britai ...

in 1978 to have been George's half-sister and not his mistress.

# Baroness Sophie Caroline Eva Antoinette von Offeln (2 November 1669 – 23 January 1726), known as the "Young Countess von Platen", she married Count Ernst August von Platen, the brother of Sophia Charlotte, in 1697.

Ancestry

Notes

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * * * * * * *External links

George I

at the official website of the British monarchy

George I

at the official website of the Royal Collection Trust

George I

at BBC History * , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:George 01 Of Great Britain 1660 births 1727 deaths 17th-century German people 18th-century German people 18th-century British people 18th-century Irish monarchs Prince-electors of Hanover Heirs presumptive to the British throne Monarchs of Great Britain Electoral Princes of Hanover Dukes of Bremen and Verden Dukes of Saxe-Lauenburg Princes of Calenberg Princes of Lüneburg English pretenders to the French throne House of Hanover Garter Knights appointed by William III Nobility from Hanover British monarchs buried abroad Burials at Berggarten Mausoleum, Herrenhausen (Hanover) Burials at the Leineschloss Osnabrück Military personnel from Hanover German army commanders in the War of the Spanish Succession